Iligan City in the shadow of the Red Sun

April 30 1942, The Japanese landed in Malabang and badly mauled Col. Eugene H. Mitchell’s 61st Infantry (PA), crossed the Mataling line and marched straight to Ganassi. There they encountered Col. Vesey’s troops. Lt. Col. Robert H. Vesey’s 73d Infantry (PA), fought well, but the Japs, supported by light tanks and artillery soon gained the upper hand. Even though, the boys of the 73rd were able to knock out a Japanese tank as it tried to cross a river.

The record of the 73rd by May 3 is one of successive withdrawals. Each time Colonel Vesey put his two battalions into position, the Japanese broke through. So closely did the enemy motorized column pursue the Filipinos that they scarcely had time to organize their defenses. By midnight Vesey had taken his men back in the hills north of Lake Lanao, where he paused to reorganize his scattered forces. The Japanese made no effort to follow. The victory was theirs and the road along the north shore lay open.

Between 29 April and 3 May, General Kawaguchi with a force of 4,852 men and some assistance from the Miura Detachment had gained control of southern and western Mindanao. Only in the north, in the Cagayan Sector, were the Filipinos still strong enough to offer organized resistance. But already on the morning of 3 May, the third of the forces General Homma had assigned to the Mindanao operation, the Kawamura Detachment, had begun to land along the shore of Macajalar Bay.

The Japanese Occupation of Iligan

By Prof. Leonor Buhion Enderes

The Japanese invaded Iligan on May 5, 1942. The Japanese occupation force, numbering about 400 to 500 soldiers did not meet any fierce resistance because the demoralized United States Armed Forces in the Far East(USAFFE)soldiers had already left. The Japanese Military Forces stationed themselves in the poblacion since this was the most accessible place, hence, it became the occupied zone. They then occupied and converted the Iligan Central School (now the Iligan City South Central School) as their garrison headquarters. Other schools were soon occupied.The St. Michael’s Academy (now St. Michael’s College) was made as training ground and sleeping quarters. The Gabaldon School (the former Boy Scout Building) was used as Japanese offices, while the Iligan Lumber Office located at the corner of Araneta Street (now the Office of Congressman Badelles) was used as the headquarters of the Bureau of Constabulary.

In occupied Iligan, Leo Garcia, Sr. was appointed Mayor till the end of World War II. Other officials were Antonio Bartolome who acted as one of the municipal councilors. Atty. Guadalupe Villanea served as the municipal judge, Dr. Godofredo Caluen as Municipal Health Officer and Zacarias Orbe as Municipal Treasurer. The local officials, however, did not have real powers. All orders came from the Japanese Garrison Commander named Captain Adachi. The local leaders were only used for espionage, labor recruitment, and food production.

The local officials were concerned about maintaining peace and order in the occupied town, and had saved many lives by establishing good relationships with the Japanese. Many times, the town mayor guaranteed the safety and vouched for the innocence of the civilians captured or suspected by the Japanese.

Aside from their usual functions, local officials maintained underground contacts with the guerrilla leaders, particularly with Pedro Andres. They secretly informed them of the Japanese plans and movements, their strength and activities.

To assist the local officials in their task of maintaining peace and order, a new police system and a self-protecting body composed of civilian inhabitants who would coordinate with the local police were organized. The police system was known as the Bureau of Constabulary (BC) while the self-protecting organization was represented by the District and Neighborhood Association (DANAS). BC posts were then stationed at the site of the Buhanginan Hill, at the pier (the present site of Pier 1), in Camp Overton, and in Tibanga (near the site of the Iligan Square Garden).

The Japanese became interested in Iligan because of the economic potentials of the area. Iligan has abundant natural resources. Added to this is the hydroelectric power potential of the area that could be harnessed from the Agus River at the site near the Maria Cristina Falls. This would make Iligan a good site for processing and manufacturing industries. It is significant to mention here that during the Japanese occupation, the Japanese showed interest to develop the Maria Cristina Falls site. In fact, they prepared an elaborate plan to build a hydroelectric plant in the area. Unfortunately, their plan never materialized owing to the progress of the Pacific War. It was because of the Maria Cristina hydroelectric power potentials that Iligan became the prime target of Japanese economic interest.

Meanwhile, in order to achieve the desired economic growth, the Japanese also looked into the condition of the other aspects of the economy such as the improvement of agriculture and other industries, the stabilization of trade and commerce and the reconstruction of other facilities.

In as much as there was a threat of shortages of food supply, the local government initiated a campaign to increase food production. To remedy the situation, Mayor Garcia exhorted all civilians to utilize every available space to be planted with basic food crops such as rice, corn, camote, vegetables and fruits. He hired civilian workers to plant crops in spaces along the roads and in the public plaza. Other areas of the town were encouraged to produce other crops. Specifically, the area of Bayug was designated to sugar cane plantation intended for the production of sugar for local consumption. A sugar mill owned by Antonio Bartolome was located in that place.

Another concern of the government was the scarcity of meat. To assure a steady supply, the local government sponsored series of dialogues reminding all animal owners of their support to one another. The local government also requested all inhabitants including the Japanese soldiers to refrain from commandeering livestock, poultry and other animals without the consent of the owners. To minimize animal deaths, the office of the municipal veterinarian was reopened. The office was responsible for the dissemination of vital information about the proper care of animals. It monitored animal diseases, at the same time, taught animal raisers some tips to prevent animal diseases, thus reducing the mortality rate. Through these measures the government was able to improve the situation.

The Japanese also tried to resuscitate domestic trade and commerce. The first step undertaken to revive what was once a flourishing trade was the restoration and maintenance of peace and order. It was followed by the reconstruction of facilities, which were blasted off by the retreating USAFFE soldiers to discourage landing of approaching enemies. Some of these were the town’s wharf, roads and bridges, the marketplace and the gas-operated electric plant. Consequently, the situation improved and the local traders started coming back and reactivated their businesses.

The center for business activities was the market place situated in the same place where the present Philippine National Bank is located, along E. Aguinaldo Street. Local traders converged here and brought their agricultural products. Some Maranao farmers also did the same. As expected, the Chinese merchants who owned big stores continued to dominate the business. The Japanese businessmen who took advantage of the time continued in their large-scale enterprises like forestry, fishing, plantation and refreshment parlors and bazaars. One of the most prosperous and successful Japanese merchants was Yamada Shiokchi. His business establishment was located at the former site of Robert Commercial, along E. Aguinaldo Street.

The currency in circulation was the Japanese money known as “Mickey Mouse.” In cases where there was lack of currency, people bartered with one another, exchanging goods that they had for whatever they needed.

On the other hand, the local government assured the people that basic commodities were available to all. Mayor Garcia initiated measures to control prices and banned hoarding of basic commodities. He instituted and ordinance on price control and on food rationing. Only those whose names were listed in the census were given ration tickets. Those with ration tickets were allowed to purchase six gantas of rice a day. To strictly enforce the law, Garcia designated Sgt. Marcos Zalsos, a BC, as Chief Economic Officer primarily to check on the prices and distribution of basic commodities. While the government apparently wanted to ensure that the basic commodities were available to all, the rationing of basic food commodities also prevented the civilians from assisting the guerrillas.

The Japanese also imposed strict control over radio broadcasts. They required owners to register their radio sets. These radio sets were reconditioned during registration to stations favorable to Japanese interest. Only Japanese broadcasts were allowed to be heard. People with unregistered radio sets were punished severely. Despite this strict imposition, a few were able to retain unregistered radio sets, which enabled them to hear news from international networks.

In the field of transportation there were no public utilities, as most vehicles were commandeered by the USAFFE before the occupation. The few other remaining ones were confiscated by the Japanese at the start of the occupation. People relied mainly on few Japanese cars called ambulancia, calesas (horsedrawn carts) and on animals like carabaos and horses to ferry them and their products to different places. Others travelled on foot. Even women walked ten or more kilometers distance in order to reach their destination.

Water transportation, too was almost non-existent. Shipping was limited to sailboats, bancas and a few Japanese ships, described by the people as bakya because their shape resembled that of a Japanese sandal. These ships frequently visited Iligan.

In the socio-cultural life, the elementary school in the poblacion was reopened and children of school age were required to enroll. Prewar subjects were taught, in addition to Niponggo and vocationalcourses. However,the impact of Japanese – sponsored education in Iligan was insignificant since not all schools were reopened for classes. Besides, only few children were able to enroll. The elementary schools in Sta. Filomena, Kiwalan, and Bayug were closed all throughout the Japanese occupation as the area was the headquarter of the 3rd Battalion, 120 Infantry Regiment, 108th Division, 10th Military District, USAFFE. These schools which were supposedly potent institutions in the cultural reorientation of the Iliganons failed because the basic principles of Japanese indoctrination were not taught and imparted to many pupils.

Col. Wendel W. Fertig (4th from left): the recognized overall commander in Mindanao by General Douglas McArthur.

Meanwhile, the women in the occupied zone, kept themselves busy doing their usual daily chores. Sometimes they attended lessons in vocational courses held at the public plaza since the local government enjoined them to attend. At other occasions, they joined social and civic activities like benefit shows and dances sponsored by the Japanese officials. Their association with the Japanese made them credible sources of information about Japanese activities, which were transmitted to the guerrillas.

However, their situation in the occupied territory exposed them to a possible sexual harassment. But the depositions of some old women revealed that the Japanese soldiers highly respected them. Some informants attested about the Japanese soldiers’ good behavior. So, there were no reported cases of women victims of Japanese sexual abuse. Although some attested to the presence of some prostitutes and a brothel for the Japanese troops situated near the present site of the Rural Transit Terminal. Most of my informants claimed there were no Iliganon comfort women. However, this did not mean that life then was easy and relaxed.

If there was anyone that everyone feared so much, it was the kempetai(the Japanese Military Police). Without warning the kempetai would enter one’s home and arrest anyone. On one occasion, the kempetai soldiers arrested Mr. Fidel Pablo who was suspected to be a guerrilla. All the residents of the town were gathered in the playground of the Iligan Junior High School to witness his execution. Mr.Pablo was hanged from a mango tree on September 28, 1942.

For the ordinary civilian especially the young people, day-to-day life had been altered by Japanese rule. On all public schoolhouses, buildings and even trees, Japanese propaganda posters were a constant reminder of the new order. With schools disrupted, there was very little for the ordinary Iliganon civilians to do at times. There would be a movie at the town plaza, but this would usually be about propaganda on Japanese capabilities. There were basketball tournaments and dances held every now and then. Other than these, there was not much that the young people could do.

While many Iliganons resisted Japanese control, there were also those who collaborated with the new colonial masters. They decided to collaborate with the Japanese for various reasons. Iligan, therefore, was not an ideal society with perfectly patriotic people. There were some who took advantage of the economic ventures and security provided by the Japanese. But willing collaboration was an exception rather than the rule because many Iliganons especially the Iligan guerrillas and their supporter still remained faithful and loyal to the Philippine Commonwealth Government.

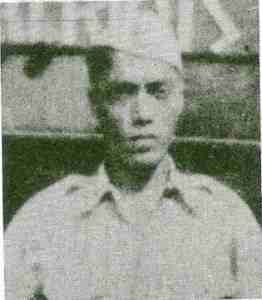

PEDRO ANDRES.“On October 24, 1942, taking cover under barbed wire entanglements and coconut-trunks-and-limestone bunker on the southern end of the old Hinaplanon Bridge, five do-or-die guerrillas led by Pedro Andres successfully stopped several truckloads of Japanese troops over the bridge. About 117 Japanese died on this encounter.”(Pedring Timonera)

The guerrilla movement started when Pedro Andres refused to heed orders to surrender. With the help of other patriotic individuals, Andres organized a guerrilla band and established their headquarters at Dawag, Sta. Filomena. Alarmed that the movement could grow into a real threat, the Japanese military force sent its troops to suppress the guerrilla band. On October 24, 1942, the guerrillas had a fierce encounter with the Japanese troops for the first time since the resistance movement was organized. In this encounter, the guerrillas defeated the Japanese forces.

The news of their triumph encouraged other patriots to organize their own guerrilla units. Guerilla groups were organized in Hinaplanon, Pugaan, Panul-iran and Pindugangan. All local guerrilla units were then consolidated into one Iligan guerrilla outfit under the command of Capt. Pedro Andres. The Iligan guerrilla outfit was later incorporated into the provincial guerrilla movement, which in turn was also incorporated into the Mindanao-Sulu guerilla movement. What made local guerrilla resistance movement very effective was the strong support from the civilian population.

The people of Iligan were surprised by the unexpected departure of the Japanese. The Japanese troops left the town on October 7, 1944, Mayor Leo Garcia, gathered all the town officials and ordered them to formally inform the people that the Japanese were no longer around and they were then free to come back to their homes. The Iliganons were so jubilant. They celebrated thanksgiving masses and held street dances to celebrate their freedom.

As soon as the Japanese troops had left, the guerrillas and the civil government officials returned to town. The Free Iligan Civil Government officials stripped off the “puppet” government officials’ authority and influence over the political and economic life of the municipality and reestablished the municipal civil government. In celebration of the restoration of the Commonwealth municipal civil government, a parade was held around the town.

During this time, Ramon Paradela served as mayor but was later succeeded by Bernardo Zosa who was appointed by President Segio Osmeña Sr. to assume as mayor. He served for less than a year, and his administration was concerned with the restoration of peace and order. It shall be noted that upon the departure of the Japanese, the collaboration question was not yet settled. Zosa dealt with this issue by establishing people’s court, in compliance with President Osmeña’s Collaboration Law. The people’s court handled all cases of collaboration and tried the various cases brought before it. Some defendants were found guilty and imprisoned. Others who were not jailed were only required to sweep all the streets around town.

But the collaboration issue did not end here for there were some guerrillas who were out for retribution against Japanese “spies and collaborators.” These Japanese collaborators sought protection from the local officials. Zosa had coordinated with various leaders to conduct negotiations and dialogues among those concerned. And the situation started to calm down.

Iligan recovered from the turmoil of the war from the time the Commonwealth Government was restored until 1950. In this year, the local leaders worked for the elevation of the municipality of Iligan to a status of a chartered city. Senator Tomas Ll. Cabili initiated the move. It was Congressman Mohammad Ali Dimaporo of the undivided Lanao who filed House Bill no.425 during the first session of the Second Philippine Congress on April 28, 1950. This bill was later signed into law as city charter by president Elpidio Quirino on June 16, 1950 as R.A. 525.